ICRISAT means business. IMOD means value chain for the poor

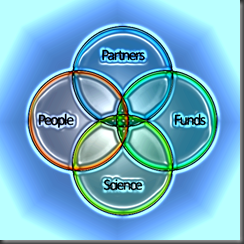

MANILA - How do you explain the success of

ICRISAT in becoming the #1 institute within the CGIAR universe of 15

international centers for agricultural research? From where I sit, it's the

positive & productive interaction of partners, people, science and funds -

none more important than the other. It was Team ICRISAT at first, led by

Director General William

Dollente Dar, working with science, people and funds. Leadership made the

local difference. Then it became Team ICRISAT & Partners. Partnership made

the global difference.

In a chain, the strongest link is the weakest; in science, that's

usually funds. In the 65th Governing Board meeting of the International Crops

Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics held at ICRISAT's campus in

Patancheru, India held 21-24 September 2011, the GB approved the Institute's

Fundraising Plan meant to set into full motion the Business Plan for 2011-2015,

considering the revised funding processes and mechanisms of the mother agency

Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research. You wait for the

protocol, but you don't wait for the funds to come to you.

To raise even more funds, ICRISAT will pursue vigorously bilateral

programs along with new partnerships to deliver science to more poor farmers in

the drylands of Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, for instance, the Institute

is laying the groundwork for the implementation of the ICRISAT South-South

Initiative, to enhance Indian-African partnerships on agricultural research for

development. R4D or applied research is what ICRISAT does best. The IS-SI was

launched during the last GB meeting in March.

Fund sourcing is an ICRISAT strength. In last month's meeting, the

Governing Board applauded Team ICRISAT in efficaciously generating funds by

packaging mega-projects such as TL II, HOPE and VDS.

TL II is Tropical Legumes II, a joint

initiative of ICRISAT

(handling chickpea, peanut and pigeon pea), the International Institute for

Tropical Agriculture (cowpea & soybeans), and Centro Internacional

Agricultura Tropical (common beans), along with national agricultural research

systems in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

HOPE refers to the project Harnessing Opportunities for Productivity

Enhancement of Sorghum and

Millets also in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. It hopes that within 10

years, the project will benefit around 2 million households in 10 countries in

Africa and 4 states in India.

VDS refers to the project Village Dynamics Studies

in South Asia. VDS gathers data & information on the consequences of

change over time (5 years) within poor villages in South Asia (India and

Bangladesh), to feed back to policymakers for appropriate Government action,

and to other decision-makers in pursuit of more precisely targeted research for

development. Without understanding the dynamics of change in those villages,

decisions for policy changes and further research can only be guesswork, based

on data that are fragmented, fuzzy and anecdotal.

I know all about anecdotal.

It has power in itself. You tell the story of a poor Asian farmer who has grown

Supercrop Z and in the last 5 years has accumulated savings in the bank to the

amount of US$ 50,000. Very convincing. He followed all the technical

instructions to the detail, followed every step, so he was successful. That's

all you tell. You don't care if he was an extraordinary individual, if many

other farmers failed doing exactly what he did, or why many farmers would or

could not follow his footsteps despite the magnetic appeal of his obvious

success. The power and danger of the anecdotal is dramatized by the fact that

one media person who actively pursued and published the anecdotal for 15 years

won an international award for journalism.

No, we cannot blame the awarding body. It wasn't the fault of the

awardee either. Surprise! In the Philippines, blame the mass media-recognized

value of anecdotal journalism on the UP College of Agriculture. I saw it with

my own eyes when the Department of Agricultural Information & Communication

of UPCA started writing and sending to Manila papers and broadcast stations

those anecdotal stories in the early 1960s. UPCA made the anecdotal look smart,

complete and commendable.

Isolated, independent, anecdotal stories mostly fail to tell of

any partnerships that have helped bring about an individual farmer's success.

Not only that. Truth to tell, the anecdotal stories from Philippine agriculture

are those of farmers who were above the poverty line from the beginning.

One of ICRISAT's legacies even now points out that journalists and

development workers cannot ignore partnerships. ICRISAT partnership is very

broad and involves 6 Ps: people, people's organizations, private companies,

political institutions, philanthropists, and patrons. Partnerships should be

embraced by journalists; why, already the list assures them at least 6 angles

for 1 story!

Why should the poor people themselves, the targets of science, be

treated as partners? They have to be because they have to contribute to the

development process; they have to contribute their share working out for their

own benefit. Mendicancy is anathema to poverty alleviation. With mendicancy,

the poor we will always have with us.

Even the poor must realize that they belong to a community whose

members must help each other. For that matter, I think that I can explain the

remarkable success of ICRISAT & partners by the workable formula of community:

(1) The Adarsha

watershed success story is

that of villagers who resuscitated a watershed and in so doing, revitalized

their own community. ICRISAT & partners brought the science in, but change

essentially began when the villagers realized the common need for them to

change.

(2) The

Agri-Science Park of ICRISAT

at its campus in Patancheru is a community of businesses being incubated and

the facilities and services necessary to transform ideas into commercial

products. Thus, from the ASP has emerged several technologies and enterprises

such as the use of sweet sorghum for ethanol production, Bt cotton, groundnut

varieties such as Nyanda (released in Zimbabwe), new chickpea varieties

released in India, and organic farming.

(3) The village

diffusion of innovation (my

term) by ICRISAT does not just help the early adoptors of technology following

the Rogers model; it has reinvented the technology adoption lifecycle initially

developed by Joe M Bohlen,

George M Beal and Everett M Rogers and later adapted by Rogers for use in

technology diffusion (Wikipedia). Thus, ICRISAT disseminates the technology to

all farmers, whole villages. Model villages are more relevant than model

farmers.

(4) The inclusive

market-oriented development strategy

of ICRISAT & partners is a virtual community of input providers, producers,

traders, processors and marketers (see my "ICRISAT's

iMODe. The village as minimum development goal," 10 December 2010, iCRiSAT Watch, blogspot.com).

IMOD is aimed at insuring that the poor producers are actively involved and

receive their proper share of the paybacks all along the value chain.

Economists thrive on theory; poor farmers thrive on actual values added to their

daily lives.

Overall, the challenge now is for ICRISAT to multiply the effects

of the community of partners, people, science and funds by including more of

the poor villagers that count in the hundreds of millions in the drylands of

many countries in Asia and Africa. Now that it is mature, "Science with a

human face" must be visited on villages upon villages of millions of

people who most need it, who must realize that change begins with them.

Comments

Post a Comment